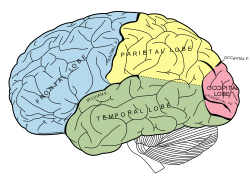

This rather shocking statement is based on an article Jason Zweig wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "Why We're Driven to Trade." Neuroscience research has shown that specific parts of the brain contribute to certain decision making. More narrowly, researchers have found that one part of the brain, the frontopolar cortex, contributes to predicting rewards.

To better understand such decision making, researchers set up an experiment with three groups: two groups without brain damage and one group with damage to their frontopolar cortex. Then, they let the three groups play a series of games where the rewards varied unpredictably.

What they found was that the two groups without brain damage tended to base their decisions on very recent data--their last two games played--whereas the group with brain damage tended to base their decisions on cumulative data of all the games they'd played. The more effective approach is to use cumulative instead of recent data.

Basically, the frontopolar cortex is a part of the brain that's used to recognize patterns. It works great when there are useful patterns to be recognized, but when no patterns exist (as they don't with random data) it goes right on recognizing illusory patterns that aren't really there.

The result is that when we run into rewards with unpredictable variability, our brains still tend to react as if it finding patterns (even though there are none). That's why people with a damaged frontopolar cortex have an advantage in dealing with such circumstances: they don't have a part of the brain that would recognize and act on illusory patterns.

This research holds lessons for investors, because investment returns--and you may have guessed this--vary unpredictably just like the game in the experiment. Like the two groups without brain damage, most people base their investing decisions on recent instead of cumulative results. This leads them to trade too frequently, selling something that has done poorly recently and buying something that has done well recently only to find what they bought does poorly and what they sold does well.

The good news is that you don't need to damage your brain to invest better. Investors who base their decisions on long term, cumulative results instead of recent data can do just as well as those with a damaged frontopolar cortex.

First, don't buy just because a stock goes up or sell because a stock goes down. That's basing your decision on recent data. Second, use long term, cumulative data to make decisions instead of short term, recent data. Third, make sure you have three reasons, outside of stock price movements, for deciding to buy or sell. And, last, keep track of your results so you can generate a cumulative record of what does and doesn't work. This is best done by keeping track of what you sell as well as what you buy.

You don't need brain damage to do better, you just need to create a deliberate decision making process that does an end-run around the part of your brain that sees illusory patterns.

Nothing in this blog should be considered investment, financial, tax, or legal advice. The opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are subject to change without notice. Information throughout this blog has been obtained from sources believed to be accurate and reliable, but such accuracy cannot be guaranteed.